Terra Nullius?

By Iris Zhai

Art critic Fred Housser (1889-1936) saw the Group of Seven’s sentimentally empty landscapes as reminiscent of the European pioneers’ first encounter with North America—“kosmos, without monopoly or secrecy, glad to pass anything to anyone—hungry for equals night and day.”[1] In this dreamy vision, Canadian citizenship is the reward for dragging the yoke tirelessly across the prairies until they are golden, or for paddling against the rapids until nature’s most deeply hidden wonders are uncovered. The hands that planted the first cross in the soil of New France would then fulfill their God-given privilege of labour—to reconfigure terra nullius (empty land) into homeland the same way God had conjured light ex nihilo (out of nothing).[2]

Yoked landscapes: Planting Potatoes, York Mills (1918) and Harvest Field (1913-17), J.E.H. MacDonald

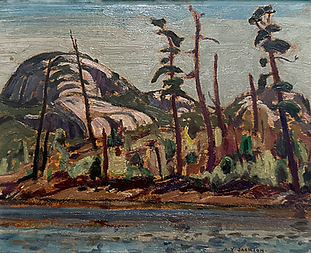

Landscapes painted from a canoeist’s perspective: Sketch for The Beaver Dam (1919), J.E.H. MacDonald; Trout Lake, La Cloche (1933-39), A.Y. Jackson; Batchawana Rapids, Algoma (1919), J.E.H. MacDonald

Parallel to the claiming of Thornhill, York Mills, Algoma, etc. as crown land via agriculture, industrialization, and commercial tourism, the Group of Seven's landscapes of the 1920s can be interpreted as labour applied in order to transform imaginary territories, thereby containing them in a visual tautology of indigenized settler nationhood.[3] Aside from the efforts of purchasing canvases and mixing colours, that is, the labour behind many of the works in the Fairley collection at the Faculty Club describes the strenuous lengths the artists would go to to make sure their audience would always imagine a land owing to Anglo-Christian Canadians for no longer being tabula rasa (clean slate). The figures of the canoeist and farmer, for instance, in The Wild River (1919) and Planting Potatoes, York Mills (1918) were careful representations of indigenized settler-Canadians—in the absence of First Nations—depicted as if they were the very first users of the oxen, plough, and canoe.

The Wild River (1919), J.E.H. MacDonald – the canoeist at the foot of the tree is not present in the sketch on the left.

Making an aesthetic into “aesthetic truth”—or, in this context, a language by which settler Canadians were able to restore pasts, imagine fellowships, and dream of futures—according to Mark Cheetham, requires a contribution of labour from the viewers as well.[4] It is up to the audience, for example, to willingly overlook that the potato farmer is a character played by Barker Fairley, or that the canoeist is likely an entirely imaginary figure.[5] Such suspension of disbelief—or, in Cheetham’s words, engagement of belief—is required for the likes of Housser to be able to imagine “his” past, “his” kosmos of infinite possibilities when looking at the Group’s landscapes. In Barker Fairley’s words, J. E. H. MacDonald was such “a native of everywhere or wherever he had lived” who would claim kinship to the Canadian Rockies “in the same exuberant vein, about pack-horses and bears and Western swear-words.”[6] Yet it is the same man who spent his childhood as an urbanite within the city and amongst cathedrals of Durham, UK, and who would never pick up swimming or paddling in Canada.[7]

Fairley’s appreciation for the Group of Seven members represents that of generations of Canadians whose families were once immigrant farmers recruited by the Union Party provincial government, whose first contact with the sacred heartbeats of nature was through camping or canoeing in summer camps, whose memory of a “national landscape” was connected to exhibitions of Lawren Harris’s icebergs inside the National Gallery of Canada.[8] Sharing a belief in the aesthetic 'truth' arbitrated by the Group was first needed as a base of collective “Canadian” consciousness during the early decades of the 20th century—made turbulent by war and rapid urbanization—but then became almost inescapable as the tautology of the indigenized Canadian crystallized into reality. What would Canada have become if Lawren Harris hadn't provided visualizations of Northrop Frye’s “great white North” as independent from European and American conceptions of beauty, or “the art of the past” that Canadian artists would seek to differ from?[9]

Behind the aesthetic of Group of Seven’s terra nullius was the artists’—and their sponsors’—nationalizing labour in emptying the land of its Indigenous history, portraying Algonquin Park as uncannily haunted by the ghosts of Algonquin First Nation peoples of a long-forgotten past, disappeared “under the penetration of trade and civilization.”[10] The tabula rasa awaiting discovery by the bush-whacking, resilient, virile settlers of Anglo-Christian descent, therefore, becomes what philosopher Marina Gržinić calls a “necrozone” where misery, exclusion, and death are manufactured for the Indigenous peoples and eventually aestheticized. This all manifests as the metaphorical suspension of Indigenous identities in an obscure time and space, in sharp contrast to the limitless agency granted to the Group of Seven in defining the “beauty and vigour of a new and untrammeled country.”[11]

What was new in the 1920s has become outdated a century later. Given that the collective imagination of Canadian identity has long been divorced from the monoracial and monotheist Northmen, a new zeitgeist must form for Canadian art as well, as Indigenous artists have long argued.[12] Real, meaningful changes (e.g., the decolonization of museums) come at an excruciatingly slow pace. Therefore, I suggest, the best response to the little-to-no changes happening would be to change the situation in which nothing happens—that is, to let changes take place first subjectively to the best of one’s ability. For example, criticizing the Group of Seven members—whether it is their art or their values—should not feel like blasphemy. That is, one might prefer to spend more time in front of the avant-garde, abstract works in the Faculty Club and not look at the landscapes. Whether the values of the past should guide the actions of the present is ultimately up to each viewer.

Notes:

[1] Walt Whitman, “Preface,” in Leaves of Grass (New York, NY: Fowler and Wells, 1855), 10. This quote was used as the epigraph to Housser’s A Canadian Art Movement: The Story of the Group of Seven, published in 1926.

[2] Whitney Bauman, “The Cogito, Ex Nihilo, and the Legacy of John Locke,” in Theology, Creation, and Environmental Ethics: From Creatio Ex Nihilo to Terra Nullius (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009), 75-7.

[3] See Lynda Jessup, “The Group of Seven and the Tourist Landscape in Western Canada, or The More Things Change …,” Journal of Canadian studies 37, no. 1 (Feburary 2002): 148-9.

[4] Mark A. Cheetham, “Truth Is No Stranger to (Para)Fiction: Settlers, Arrivants, and Place in Iris Häussler’s He Named Her Amber, Camille Turner’s BlackGrange, and Robert Houle’s Garrison Creek Project,” in Unsettling Canadian Art History, ed. Erin Morton (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022), 142.

[5] Fairley’s words: “it might be me again, following the plough … at least there is no one left to dispute the claim.” Barker Fairley, “A note on the Pictures,” in Collection of Pictures Presented to The Faculty Club (Toronto, ON: Faculty Club at the University of Toronto, 1990).

[6] Barker Fairley, “J. E. H. MacDonald,” in A Loan Exhibition of the Work of J. E. H. MacDonald (Toronto, ON: Mellors Galleries, 1937), 4-5.

[7] Liz Wylie, In the Wilds: Canoeing and Canadian Art (Kleinburg, ON: McMichael Canadian Art Collection, 1998), 12-3.

[8] Scott Watson, “Race, Wilderness, Territory and the the Origins of Modern Canadian Landscape Painting,” Semiotext(e) 6, no. 2 (1994): 99-100.

[9] On popularization of the “Great White North” national myth, see ibid., 94-9; the foreword to the brochure that accompanied Group of Seven’s very first exhibition at the Art Museum of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) made the bold statement that “this art will differ from the art of the past, and from the present day art …” See Catalogue Exhibition of Paintings: May 7th - May 27th 1920 (Toronto, ON: Art Museum of Toronto, 1920).

[10] From the brochure that accompanied the famous “Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern” hosted by the NGC in 1927 under director Eric Brown, who wrote “the disappearance of these (Indigenous) arts under the penetration of trade and civilization is more regrettable than can be imagined …” Brown was one of the most prominent sponsors of the Group of Seven, responsible for the nation-wide recognition of their “modern” genre of landscape paintings. Eric Brown, foreword in Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern (Ottawa, ON: National Gallery of Canada, 1927).

[11] On "necrozone," see Marina Gržinić, “What Is the Aesthetics of Necropolitics?” in The Aesthetics of Necropolitics, ed. Natasha Lushetich (London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 17; the quote on G7 is from the brochure that accompanied Group of Seven’s exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 1921. An Exhibition of Canadian Paintings by the Group of Seven: December 1921 (Minneapolis, MN: The Minneapolis Institute of Art, 1921).

[12] See Tatum Dooley, “The Group of Seven Doesn’t Define Canadian Art,” The Walrus, February 19, 2021, https://thewalrus.ca/the-group-of-seven-doesnt-define-canadian-art/, and Sky Godden, “A Rebuttal, Not a Conversation: Discussing Ombaasin’s AGO Intervention, ‘Land Rights Now,’” Momus, June 23, 2015, https://momus.ca/a-rebuttal-not-a-conversation-discussing-ombaasins-ago-intervention-land-rights-now/.